Imagine two different societies. In the first, people tend to be stressed, tense, irritable, distracted and self-absorbed. In the second, people tend to be at ease, untroubled, quick to laugh, expansive and self-assured.

The difference between these two imagined scenarios is vast. You’re not only more likely to be happier in the second scenario – you’re also more likely to be safer, healthier and have better relationships. The difference between a happy and an unhappy society is not trivial. We know that happiness matters beyond our desire to feel good.

So how can we create a happy society? The Buddhist nation of Bhutan was the first society to determine policy based on the happiness of its citizens, with the king of Bhutan famously claiming in 1972 that Gross National Happiness (GNH) was a more important measure of progress than Gross National Product (GNP).

Many other countries have since followed suit – looking to move “beyond GDP” as a measure of national progress. For instance, the UK developed a national well-being programme in 2010 and has since measured the nation’s well-being across ten domains, not too dissimilar to Bhutan’s approach. More recently, New Zealand introduced its first “well-being budget”, with a focus on improving the well-being of the country’s most vulnerable people.

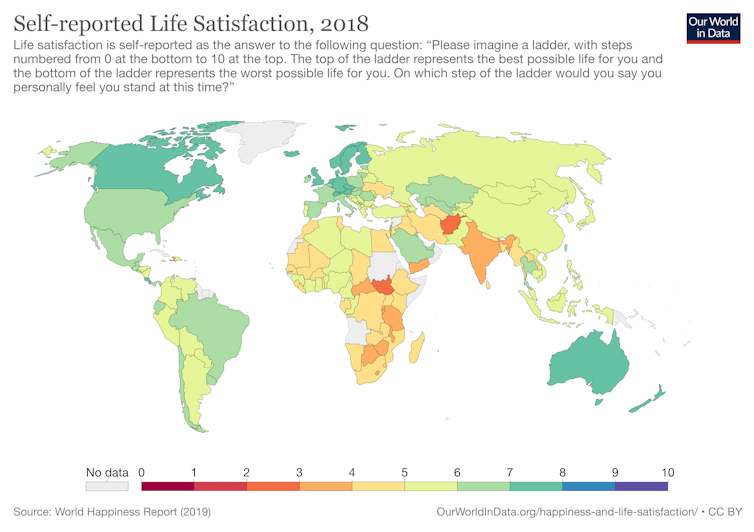

Such initiatives tend to broadly agree over the conditions required for a happy society. According to the World Happiness Report, there are six key ingredients for national happiness: income, healthy life expectancy, social support, freedom, trust and generosity. Scandinavian countries – which typically top the global happiness rankings (Finland is currently first) – tend to do well on all these measures. In contrast, war-torn nations such as South Sudan, Central African Republic and Afghanistan tend to do badly. So does happiness rely on these six key ingredients?

The what, not the how

I don’t think so. This approach is, ultimately, too simple – even potentially harmful. The problem is that it focuses on what happiness is, not how to achieve it. Clearly, things such as a good life expectancy, social support and trust are good for us. But how we come to that conclusion may matter more than the conclusion itself.

For instance, how do we know that we are measuring what is most important? The world happiness rankings largely rely on measures of life satisfaction. But it is far from obvious that such measures can account for important differences in emotional well-being.

Alternatively, perhaps we could ask people what they think matters. The development of the UK’s national well-being programme took this approach, undertaking qualitative research to develop their ten domains of happiness. But this approach is also problematic. How do we know which of the ten domains are most important? The most important ingredients for one community may not be the same for another. Asking people is a good idea. But we can’t just do it once and then assume the job is done.

Don’t get me wrong – I believe these kinds of initiatives are an improvement on more narrow ways of measuring national progress, such as an exclusive focus on income and GDP. But that doesn’t mean we should ignore their faults.

There are parallels here with the pursuit of happiness on an individual level. We typically go about our lives with a list of things in our head which we think will make us happy – if only we get that promotion, have a loving relationship, and so on. Achieving these things can certainly improve our lives – and may even make us happier.

But we are fooling ourselves if we think they will make us happy in a lasting sense. Life is too complicated for that. We are vulnerable, insecure creatures and will inevitably experience disappointment, loss and suffering. By exclusively focusing on the things we think will make us happy, we blind ourselves to the other things in life that matter.

Happiness 101

Psychologists are beginning to focus their attention not just on the ingredients of individual happiness, but also on the capacities people need to be happy within inevitably insecure and fragile circumstances.

For instance, the so-called “second wave” of positive psychology is as interested in the benefits of negative emotions as positive ones. The mindfulness revolution, meanwhile, urges people to go beyond their notions of good and bad and instead learn how to accept things as they are. These approaches are less concerned with what conditions make people happy and more interested in how people can pursue happiness within conditions of insecurity and uncertainty.

The more we focus on our list of desired things, the more we fail to see what really matters. When we are certain of the things that make us happy, and urgently try to achieve them, we fail to appreciate the value of the things we already have and the multiple unknown opportunities we have yet to discover. When things inevitably go wrong in our lives, we blame others or ourselves instead of learning from what happened.

Psychologists are beginning to understand the limits of this. Happy individuals tend to have humility as well as certainty; curiosity as well as urgency; and compassion as well as blame.

We can apply these same lessons on a national scale. Creating a happier society requires not just promoting what matters, but also promoting the capacities for discovering what matters.

We know this on an institutional level. In education, we know that it is important to promote curiosity and a love of learning as well as good exam results. In academia, we know that, although we can discover important scientific truths, almost all of our current scientific theories might be surpassed by other theories and we should remain open minded. We know that the appeal and relevance of religious institutions depends on balancing dogmatic teachings with mystery and curiosity – order and faith on the one hand, openness and flexibility on the other.

Creating a happy society does not just depend on creating the right conditions. It also depends on creating the right institutions and processes for discovering those conditions. The irony is that members of the happy society described at the beginning of this article – who tend to be at ease, untroubled, quick to laugh, expansive and self-assured – are probably less focused on what makes them happy and more focused on exploring what really matters – with humility, curiosity and compassion.

To actually create a happy society, we need measures and institutions that do much the same.

Sam Wren-Lewis, Honorary Associate Professor in Philosophy, University of Nottingham

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.