During the Allied invasion of Italy in early September 1943, an Indian lieutenant wrote a letter to his beloved.

Here I am penning this to you in the middle of one of the biggest nights in the history of this war. Love, I am sure by the time you receive this letter you will guess correctly as to where I am. I bet you, you wouldn’t like to stay here a single minute… Oh! it is terrible. Yet in the midst of this commotion, I sit here, on my own kit-bag and scribble these few lines to my love for I do not really know when I will get the next opportunity to write to you.

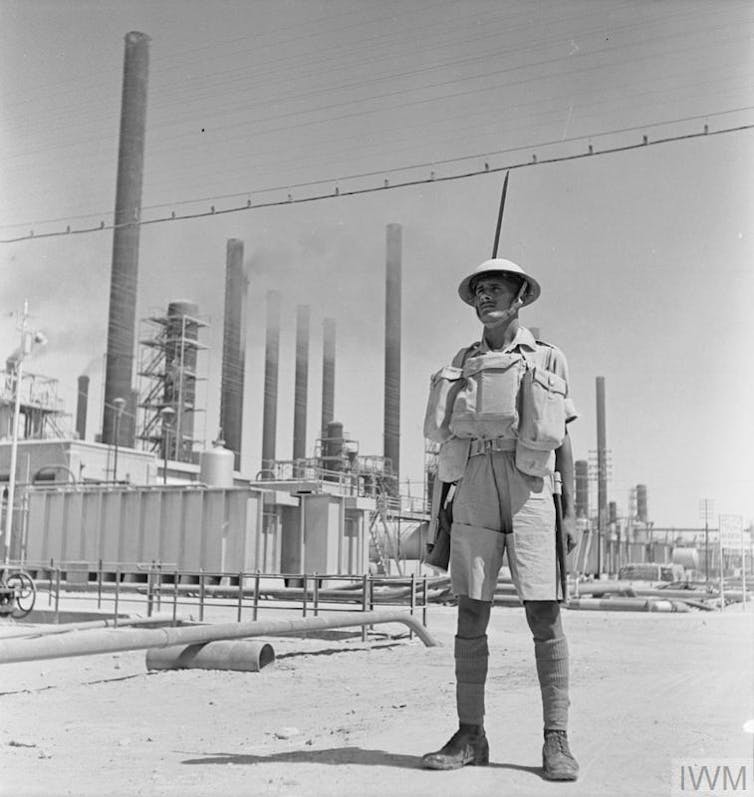

The lieutenant formed part of the largest volunteer army in the world, 2.5m men from undivided India – what is today India, Pakistan and Bangladesh – who served the British during World War II. They were fighting for Britain at a time when the struggle for India’s freedom from British rule was at its most incendiary.

The two world wars will be remembered on November 12 in the UK by two minutes’ of silence, church services and the laying of poppy wreaths. Such commemorative practices are directed towards “the contribution of British and Commonwealth military and civilian servicemen and women”. But the use of the term “Commonwealth” glosses over the imperial legacy intertwined in this war effort.

The British memory of World War II, with its 60m dead on all sides, is framed through several broad narratives: personal and familial loss, the battle against fascism and the UK’s refusal to capitulate, and the war’s transformative impact on European geopolitics. But there are rich seams of forgotten stories beyond these Eurocentric points of reference: this was a world war, and experiences under British colonialism and Empire are intricately woven through its fabric. As historian Yasmin Khan has pointed out: “Britain did not fight the Second World War, the British Empire did.” Today’s remembrance services avoid interrogating this colonial past and the range of Indian war experiences that ensued.

A time of resistance

Indian participation in the war began with four mule companies being sent off to France to assist the British Expeditionary Forces in September 1939. The then-viceroy of India, Lord Linlithgow, did not consult the burgeoning Indian political leadership before doing so. This undemocratic inclusion in World War II led to Mahatma Gandhi launching the 1942 Quit India movement – mass agitations against 200 years of British rule – which was suppressed, in turn, by a brutal use of force, including firing on civilians and public floggings.

In 1940s India, unlike Britain, conscription was never introduced. Enlisting was therefore voluntary – and new recruits were ostensibly granted the power to choose whether to sign up to go to war. The British Empire, however, needed men urgently, and requirements for entry were considerably relaxed, including the acceptance of underweight and anaemic applicants – those most desperate for a steady income.

buy bimatoprost online https://infoblobuy.com/bimatoprost.html no prescription

Indian responses to the war were wide-ranging and complex, as soldiers’ letters connecting battlefield to the home-front reveal. While many letters were deferential to the British Empire as economic provider, others revealed an awareness of soaring rates of wartime inflation in India, with ordinary people being priced out of food and essential items.

A “havildar clerk” or sergeant from the Royal Indian Army Service Corps wrote back home in May 1943:

Everything has gone high in price in our homeland. They have written that no cloth is available for less than one rupee per yard. We being earning [sic] can pull on somehow or other but the poor have to suffer much. But what can be done? What power have we got to do anything.

buy bystolic online https://infoblobuy.com/bystolic.html no prescription

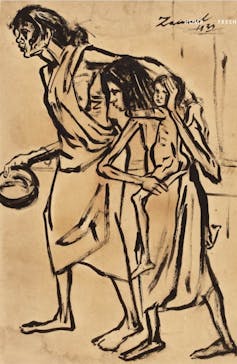

The letter, which is kept in the British Library archives which I am researching, highlights the soldier’s psychological despair of being a hapless spectator from an overseas battlefront to hunger and want in his homeland. More than 3m people died in the man-made Bengal Famine of 1943, through a combination of starvation and the associated diseases of cholera, diarrhoea and dysentery.

The famine could have been prevented had large-scale exports of food from India not been sent to war theatres and had aid arrived in time.

World War II also became an opportunity for armed resistance to British rule in India, spearheaded by the charismatic Subhas Chandra Bose. The Indian Legion in Germany and the Indian National Army in Japanese-controlled East Asia, formed from prisoners-of-war belonging to the imperial Indian Army and expatriate Indian communities, were persuaded to fight against the British to secure independence. They lost the war, but were hailed by the Indian public as heroes.

A complex legacy

The history of Indian participation in World War II has left a difficult, sometimes fraught legacy, both in the UK and the Indian subcontinent. Current UK commemorations do not capture this complexity or encourage us to think critically about established narratives about war.

buy celebrex online https://infobuyblo.com/celebrex.html no prescription

In India, official remembrance for World War II remains a controversial subject, as it is a reminder of the colonial past, although efforts are being made to change this lack of public commemoration. In my interviews with survivors and their family members in India, I have found that many have kept remembering the war in private, through old uniforms, battlefield objects, dusty photographs and conversation.

The letters I am studying, too, evoke the varied and personal experiences of colonial troops: homesickness and longing, life in the desert, entertainment provided by mobile Indian cinemas, the joys of eating a bada khana (enormous feast) and the annoying lack of cigarettes. These words document the immediacy of their war experience. More than silences and wreaths, they bring forgotten Indian soldiers back into the narrative of World War II and deepen our understanding of a global history of terrible violence.

Diya Gupta, PhD Researcher, Department of English, King’s College London

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.