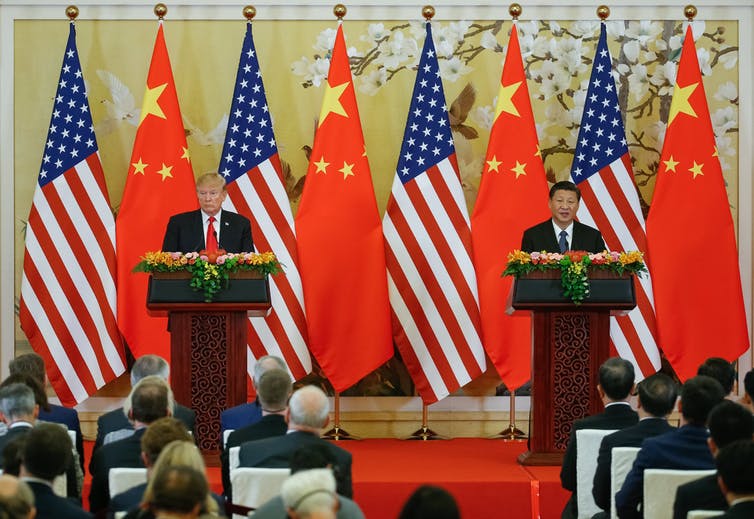

AAP/EPA/Roman Pilipey

Donald Trump is making good on his trade war rhetoric with China, announcing tariffs on a further US$200 billion worth of goods from the PRC. As China promises retaliation, the warmth of the Mar-a-Lago summit of April 2017 is a thing of the past. When this is added to the wide-ranging tensions such as the disputes over barely habitable rocks in the East China Sea, tensions over the competing claims in the South China Sea, and the spectre of nuclear catastrophe on the Korean Peninsula, the sense of geopolitical risk is as palpable as it is frightening.

During such periods of turbulence, it is not surprising that scholars and commentators look to the past for parallels to current crises. Not long ago, the trend, prompted by the centenary of the outbreak of the first world war, was to see Asia on the cusp of 1914-like conflagration. This proved a highly imperfect point of comparison.

Today, a more common refrain is that Asia is on the cusp of a new Cold War. If it were to happen, it would mean the rivalry that has been growing is transformed into overt militarised competition that drags the region into its vortex.

In this case, the US is confronted not by an expansionary Soviet Union seeking to capitalise on decolonisation to advance its ideological and geopolitical ambition, but by a resurgent China. Its ambitious president, Xi Jinping, has clearly set out his aim to make China the world’s preeminent national power.

Until very recently, it seemed unlikely that a Cold War with 21st century characteristics would eventuate. The USSR and United States inhabited almost entirely separate economic universes during the Cold War.

This meant the dynamic of competition was driven by power politics and ideology alone – the tempering effect of shared economic interests simply didn’t exist. Today, so the argument goes, their economic interdependence is a powerful brake on the worst instincts of the two countries.

While China and the US are in competition, the two countries have also established an extensive range of bilateral mechanisms to manage their complex relationship. There are around 1000 meetings between the countries every year, ranging from summit level down to mid ranking officials, covering issues from trade and investment to coastguard and fisheries.

The two countries know they have to work hard to ensure the competitive dynamic does not spiral out of control. And of course, both sides’ nuclear weapons act as a great disciplining force, ensuring even the most heated of relationships can remain short of outright conflict. Asia also has a wide array of institutional mechanisms such as ASEAN and the East Asia Summit that regularly discuss their common concerns and build a sense of regional trust.

Yet, in spite of their many meetings, in which there is much discussion but little agreement, there are good reasons to think a Cold War 2.0 might be a good deal closer than we realise. The US and China are plainly entering into a period of significant geopolitical rivalry. Each has ambitions that are mutually incompatible. Beijing wants a south-east Asian region in which it is not beholden to US primacy, while Washington wants to sustain its regional dominance.

The two also find it extremely difficult to see the world from the other’s perspective. Washington does not seem able to grasp that even though Beijing benefited from US primacy in the region, it will not forever accept a price-taker’s position in the regional order.

For its part, Beijing simply does not believe Washington’s claim that it wants China to achieve its potential, and that this can occur without meaningful changes to the current international order. When that is added to the nationalism that is a powerful political force in both countries, the prospects of a bleak geopolitical future seem very real.

The trade war escalation is one of the most worrying developments. Not only does it signal a more turbulent and less dynamic period in the global economy, it represents the victory of nationalist politics over shared economic interests. More importantly, it may presage a return to a less integrated global economy.

Trump evidently wants to rip up global supply chains and turn back the clock to the days of mercantilist approaches to economic development. Most worryingly, due to China’s behaviour in the past — stealing IP, predatory approaches to foreign investment and refusing access to its vast markets — Trump’s tariffs have a surprising level of support in business circles in the US.

The risk is not only one of sustained tension between the world’s biggest economies, but significant division between the interests of the two most important countries. If the golden straitjacket of economic interdependence is gone, the prospects of geopolitics and nationalism winning the day are significantly enhanced. China also sees in the tariffs a confirmation of its long-held suspicion that the US is intent on keeping the country from fulfilling its potential.

Worryingly, there is widespread complacency in the region. We used to think great power politics had been banished by globalisation. We were wrong. We thought Trump would come to his economic sense when elected. Wrong again. And now the escalation of trade conflict is undermining the most important link between the US and China – their shared economic interests.

We must not fool ourselves again. High intensity geopolitical competition is increasingly likely. Unless the US and China can step down from the escalatory cycle they are on, we are sliding into another period in which great power rivalry, militarised competition and dangerous nationalism once again dominate the region.![]()

Nick Bisley, Head of Humanities and Social Sciences and Professor of International Relations at La Trobe University, La Trobe University

This article is republished from The Conversation. Read the original article.

buspar no prescription

buy Strattera online

Nexium no prescription