From New York to Moscow, Johannesburg to Buenos Aires, the novel coronavirus continues its global journey. On March 30, almost three months after China announced the discovery of COVID-19, the disease associated with the coronavirus, more than 780,000 people have been infected and at least 37,000 have died.

While the epidemic appears to be under control in China, the US is now the country most affected by the pandemic. In Europe, it would appear containment measures and lockdowns are beginning to bear fruit: in Italy, the figures indicate a slowdown in the number of infections.

All over the world countries are locking themselves off one after the other, closing their borders and confining their populations more and more drastically. The World Health Organization has welcomed these efforts. The world is slowing down and holding its breath. For how long?

As researchers around the world continue to decipher the consequences of this unprecedented situation and to seek solutions to the crisis, The Conversation’s international network continues to work with them to inform you as best as possible.

The fate of the epidemic

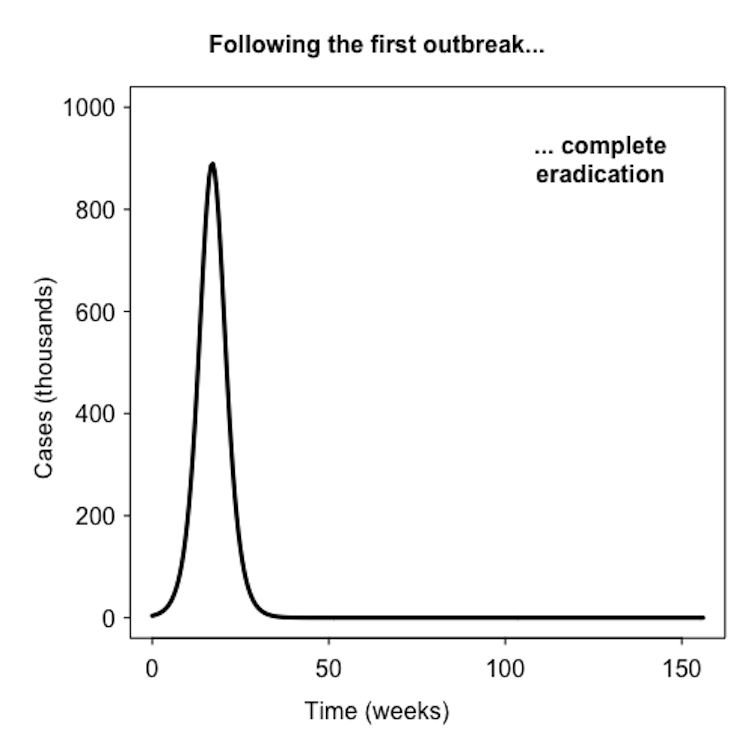

How long will we have to live with COVID-19? Could it possibly return? The history and modelling of epidemics can help find the answers.

- Modelling past major epidemics can show how this one will unfold. This is what Adam Kleczkowski at the University of Strathclyde and Rowland Raymond Kao at the University of Edinburgh have done.

- Mathematical models. Christian Yates at the University of Bath explains how epidemiologists create the models to predict the course of an epidemic, which are essential tools for informing governments’ actions.

- Anticipating epidemics. According to Éric Muraille at the Université Libre de Bruxelles, history teaches us epidemics are inevitable. This is why it is essential to know how to anticipate them (in French).

The fate of the pandemic will obviously depend on the weapons at our disposal to fight the coronavirus.

- Chloroquine? Parastou Donyai from the University of Reading explains that although much has been written about the anti-malarial drug, there is as yet no evidence of its effectiveness in preventing COVID-19.

- Therapies and vaccines. Ignacio López-Goñi at the University of Navarra lists the different therapeutic trials currently underway and says there is hope for therapies to treat patients or vaccines to prevent infection.

The coronavirus pandemic must not be allowed to overshadow other deadly diseases.

- Tuberculosis and AIDS. Emily Wong at the University of KwaZulu-Natal draws attention to the fact that in South Africa, COVID-19 is adding to existing epidemics. Experts are concerned these patients are more at risk of developing severe forms of the disease.

A disease of biodiversity

Like many infectious diseases that affect humans, the COVID-19 pandemic is a zoonosis: the virus that comes from animals.

- Bats? – Once again, this new virus probably originated from a bat. Eric Leroy at the Institut de recherche pour le développement explains why these mammals are a “usual suspect” for the transmission of viruses to humans (in French).

- But it’s unfair to blame them, because they do us important services and must be protected, says Peter Alagona at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

Rather than blaming these flying mammals, we’d be better off questioning our relationship to nature and biodiversity.

- The symptom of a global environmental crisis? It could well be, write Philippe Grandcolas and Jean-Lou Justine at the Muséum national d’histoire naturelle (MNHN) (in French)

- “This is not a tragedy for everyone. Some of our neighbours are doing better since we have retired to our apartments”, writes Jérôme Sueur at MNHN. Less human activity means less noise, which is actually a good thing for birds in our cities, in particular (in French).

Lockdown left behind

More and more of us are being confined in the hope of limiting the spread of the virus and relieving the unbearable strain on health systems. But not everyone is equal when it comes to lockdown and quarantine measures. Some groups are particular at risk.

- Elderly or disabled people. In medical-social institutions, those who are already vulnerable are the big losers of containment measures, writes Emmanuelle Fillion at École des hautes études en santé publique (in French).

- Prisoners. (in French) This is also the case of prisoners, whose fate worries the prison administration because of their proximity to the prison.

- Those who can’t be confined. Alex Broadbent and Benjamin Smart at the University of Johannesburg point out that some cannot be locked down, or even implement adequate social distancing measures.

In addition to the risk of lockdown, heads of state face political risk: their every move is scrutinised and commented upon.

- The South African President Cyril Ramaphosa is no exception, explains Richard Calland at the University of Cape Town, but so far his government’s lockdown measures seem adequate, writes Philip Machanick at Rhodes University.

- Conversely, as the epidemic is just entering a phase of exponential growth in Indonesia, Iqbal Elyazar at the Eijkman-Oxford Clinical Research Unit and his colleagues are urging the government to take tougher measures to avoid disaster.

- In France, Catherine Le Bris at the Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne wonders how to reconcile emergency situations, the limitation of freedoms and the rule of law. The balance lies in the respect of human rights she argues (in French).

– Finally, Michael Baker at the University of Otago returns to the essential point of all these efforts: to control the pandemic. He is a professor of public health and is “overjoyed” that shutdowns are happening.

Revealing inequalities

The current pandemic is also exacerbating inequalities.

- Panic buying. James Lappeman at the University of Cape Town has focused on the panic buying triggered by the coronavirus panic. But this sheds a harsh light on economic inequality.

- Inequality. Pandemics reveal inequality as never before, and South Africa is a textbook case of this, according to Steven Friedman at the University of Johannesburg.

But the current crisis could also be an opportunity to explore ways to reduce inequalities and to test new approaches, particularly economic ones.

- “Helicopter money”, a theory coined by the economist Milton Friedman in the 1970s, could be used to reduce inequality by distributing money directly to the population, explains Baptiste Massenot at TBS Business School (in French).

And finally, as a tribute to the “heroes in white coats”, The Conversation has published a series of testimonies from clinicians and researchers operating on the front lines of the pandemic – and providing advice on the conversations we should now be having with our loved ones.

Lionel Cavicchioli, Chef de rubrique Santé, The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Also Read: Coronavirus Myth VS Facts From WHO – World Health Organization

Also Read: Are You in Danger of Catching Coronavirus: 5 Questions Answered